“I’ve always told people that when you have a movie that’s fairly complicated be sure to have a talking pug dog in it, because then you can fix things after with the same pose.” – Eric Brevig, Men In Black visual effects supervisor

Twenty years ago, Barry Sonnenfeld delivered the quirky action sci-fier Men in Black, starring Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones, to adoring audiences. It is a film also adored for its combination of practical and digital effects, mixing Rick Baker’s makeup and creatures through this Cinovation Studios, with Industrial Light & Magic’s CG and miniatures handiwork. Several other studios – practical and digital – also contributed.

To celebrate the film’s two decade anniversary, vfxblog spoke to visual effects supervisor Eric Brevig about Men in Black’s aliens, humans who are actually aliens, and about the range of models and miniatures used in the show. We also dive into the major plot changes and plot fixes enabled via visual effects, plus the secrets Brevig learnt from Sonnenfeld in making comedic moments.

vfxblog: It’s been 20 years since the film came out, but what do you remember most about Men in Black and its visual effects legacy?

Eric Brevig: Well, kind of the most satisfying for me was realising we were definitely at that sweet spot between practical and digital effects. I think since then the industry sort of was swinging too far in one direction, and now it seems like it’s kind of levelling out at once again and saying, let’s use the best technique for what we need to do. If you have that sense of, let’s try to make things look photographic rather than computer graphic, or video game style, or whatever, I think it allows the audiences to identify with the story, and kind of get lost in it to a greater level.

And I think that’s one of the real charms of the movie is that everything is so over the top, and so almost cartoony in the action, but yet you genuinely feel like its all been filmed by real people undergoing the stuff by a real movie crew. That’s one of the things that I think I’m the most proud of.

vfxblog: Let’s talk about one of the first characters that audiences see, because I think that it was this great combination between on-set work, and practical and digital, and that is Mikey, when they’re picking up the asylum seekers. How was that character was approached from an effects point of view?

Brevig: Rick Baker was involved on early and designed the look of all of the creatures. He made a facsimile of the actor’s head that you see Mikey holding on a stick. The Mikey that we saw in the film is essentially a CG character. But Rick did build a bunch of prosthetic and mechanical creatures, especially for the MIB headquarters, and sometimes we would hand off between practical and CG, like the worm guys. Some scenes were puppeteered creatures and others were CG versions of the same characters based on what the needs of the story were, but it was his designs.

The only one really that was mostly fully CG and an unpleasant surprise, certainly for Rick, was that the story changed enough that the Edgar creature that he built, which was this magnificent full-sized marionette creature, couldn’t do what the story needed, which was basically to swallow Tommy Lee Jones, because the head was just too small. Unfortunately that one isn’t seen in the movie, and we built a similar but different proportioned and slightly differently designed CG version of him, and that’s what you see in the film.

vfxblog: So many people remember the Edgar bug – it was such a detailed character and so well animated. Can you talk more about bringing that to life?

Brevig: Yeah, I’m glad you noticed that. The detail work, and the textures, and the performance as well as just the oozing skin and moist texture, those were all very new pieces of software. ILM had wonderful animators and our animation supervisor Rob Coleman did an amazing job. I think we all really enjoyed the character because his actions are so big, and sinister, and funny, it’s really a pleasure to do a character that’s sort of larger than life. Even though he is a big character, his performance is even bigger. The fact that he swallows Tommy Lee Jones, and then has to explode…

I asked Peter Chesney, who was the physical effects supervisor, to build a big exploding gut thing so that we could have that as a physical event that we would shoot. Then we put in the creature for that moment around it, as well as enhancing it. It’s pretty common now, but my approach was anything that’s gonna be a CG effect we want to have some graphic element of it, whether one leads the other it doesn’t matter, but it’s a combination of both. I think the Edgar bug is a great example.

vfxblog: I still think the transformation from Vincent D’Onofrio to Edgar bug is such a well designed sequence, in that you don’t see everything, but you see enough to know that it’s happening.

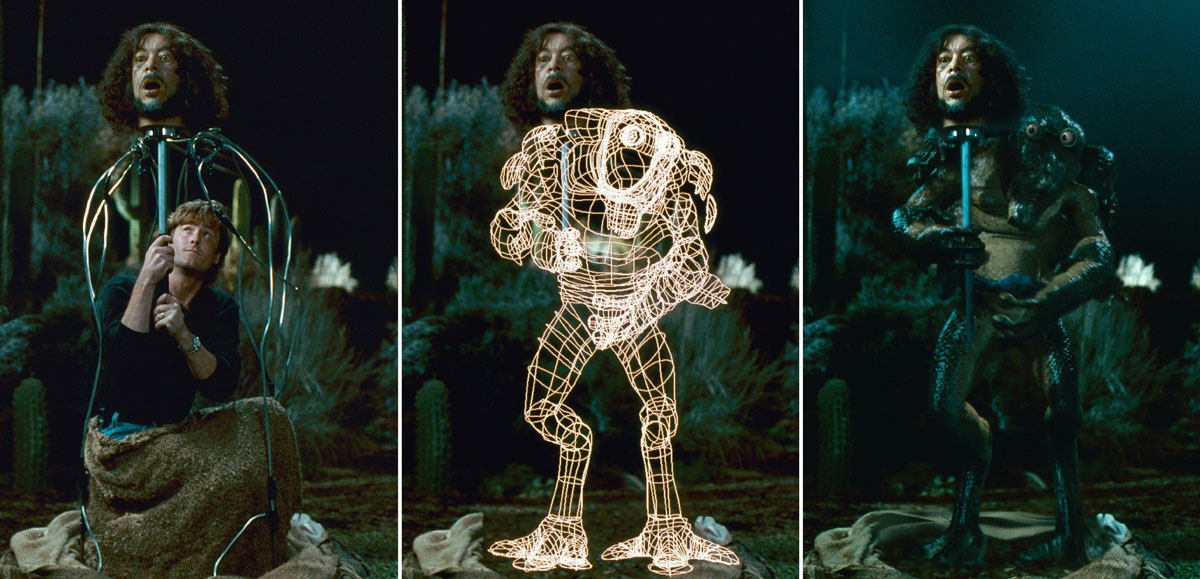

Eric Brevig: Yeah, it was definitely a combination with Rick, Edgar, and the makeup they did on him. The idea was, when he decides to reveal himself they did a special version of his makeup that was a very stretchable. What he does is he grabs the back of his head and he just starts tugging on it. The idea was he would pull it as far as he could, and then we would take over stretching the image, making it appear to be distorting in a way that it physically couldn’t. Much the way we did the Tony Shalhoub alien who they shot in the head. You have a real human actor underneath there, and then you just start to take over and distort that at the right time.

Then basically when I shot Vince I just kept urging him to pull harder, and harder, and harder until finally the final take he just pulled it until the makeup just ripped. We said, ‘Okay, we got it.’ That’s what’s in the show because it’s really tugging on his face the maximum it could be done, and then we just extended that. Helped by a little bit of editing we were able to put a ridiculously large CG creature inside of a human sized body, and we’re not seeing it all at one time, you kind of get away with the fact that, well maybe he was in there he was just hunched up.

There’s a certain amount of conceit that we get away with things that aren’t completely believable, but I think that’s part of the fun of the movie. A lot of the action and events are fantastic and over the top, but really done with a lot of glee and humour.

vfxblog: One of my favourite shots with Edgar bug is when Will Smith steps on the cockroach and the camera zooms into Edgar as he spins his head around. And I remember watching this in 1997 thinking, ‘Wow, we really are getting a lot of personality from a CG character here.’ What kind of discussions were you having about getting that personality from a digital creature

Brevig: Well, with several important dramatic events in the film the camera does a very fast push in to the character. It happens when Will steps out in his Men in Black outfit for the first time. It’s a convention that Barry loves to use, and really works great. So we were remaining consistent with the style of the photograph. It’s a little bit cartoony, but that’s okay because that fits.

In terms of the personality, luckily when we were tasked with revising Edgar bug to be able to do some different things we were able to give him a really expressive face with eyes, and eyebrows, and forehead, that would really be able to just scowl. The reason we did that was just for the end sequence, so he could just become completely enraged.

vfxblog: You mentioned Tony Shalhoub’s character, that’s Jeebs, who gets shot in the head and re-grows there. That was also such a memorable morph and transformation. Can you talk about the challenges of doing that at the time?

Brevig: We shot Tony until the moment he was supposed to have exploded as just an actor. I think he had big ears, and a contact lens that made his eyes not be pointing in the same direction. Then at the moment he got shot we basically covered his face in slime and I just had him act it as though his face were painfully reforming from a tiny little embryo head. That was the conceit of what happens, when you get shot you have to reform. Then we obviously erased his forehead and built a model of a CG head that could be scaled and animated like it was going through all sorts of birthing pains.

About halfway through we started mapping the textures of Tony’s face on to it, so that by the time it’s stretched and distorted, and so forth, it’s back to looking like him. For that shot, even though it looks like him it’s still a CG head, and so we cut away and then we cut back. Instead of morphing his image we’re basically doing it as a CG model that is designed in many stages to transform from one to another. It doesn’t feel like it’s a photographic trick, it feels like it’s an actual animated event. And the fact that he was acting underneath all that allowed us to really have fun with a couple of very goofy expressions along the way.

vfxblog: And just still while we’re talking about aliens, what about the worm guys? I’m interested in how they were both real puppets and CG creations.

Brevig: We took the puppet models or maquettes for them, and just cyber scanned them on a turntable, then those became the shell of the model of the thing we would build. They were live puppeteered essentially, when you see them in the coffee room early in the movie they’re all attached to the set, there’s puppeteers hiding behind the set and so forth. But the model design is completely worked out. Once you scan those and you build them as full CG models, and textured them, then you’ve got the ability to have them walking around in the open, which is what we did later in the show, and you see them, I think, walking around the headquarters and so forth, they’re the CG version.

But unless you know that intellectually you can’t tell, because we did a lot of side-by-side studies of the puppet version on a turntable next to the CG version on a turntable, and had them match precisely in terms of colour and shade, so that the CG ones were pretty spot on. It helped that we had the animatronic versions there to photograph on the set as exact reference of what they should look like, so that the ILM versions are pretty indistinguishable.

vfxblog: There’s also such great craftsmanship for the Arquillian alien you see in the morgue, which is inside the head. And what I loved about that, I remember 20 years ago, was not realising that there were different scale models of it, for close-ups. Tell me about the design and how that sequence played out.

Brevig: We went through a lot of ideas. I’m a big fan of photography, and Rick certainly has the talent to be able to build things that would look exactly like what they need to look like. The scale of it was impossible to build something inside that had that detail, it would be too tiny to fit inside an average human size head.

We decided that he would build a one-to-one scale of the dead man’s head that would be able to open, but inside of it would be something that I would shoot that he and his guys would puppeteer, but at a much larger scale that would be optically shrunk and put into the head. Everything you see looks correct, but it’s done the same way you would do a tiny person. That allowed us to have full control over both the normal size head and the miniature alien inside, and it was kind of the best of both worlds.

vfxblog: The cross-over between practical and digital is really a big part of the film, isn’t it?

Brevig: Yes, Rick was just beginning to use digital tools as kind of a way to pre-visualize what his makeup was going to do. Because we were using both photographic techniques and digital techniques, like anything was open. I remember Rick did a demonstration of a pug makeup on an actor. Eventually we decided that it wasn’t really the best way to go and we should just use a real dog and modify the face, but it was really fun to see an actor in a muzzle much like sort of traditional prosthetic makeup on a human, and be able to at least evaluate that.

These days you would never think of even trying that, but there’s a tangibility and authenticity about actual photographic efforts and performances, especially the kind of fantastic humorous characters that I really enjoyed the opportunity to work with Rick and come up with ideas that hadn’t been done before.

vfxblog: And with the pug I was just thinking I’d almost forgotten that that sequence is a visual effects one, because there’s just such a variety of work that you had to do in the film. Obviously some things had been done with Babe at Rhythm & Hues and other films before with talking animals but was this the first time ILM tackled that kind of work?

Brevig: It was, and it was quite challenging because a pug dog, as I learned as we were trying to analyse what they really look like, and how their mouths look, but it’s such a complex creature. I remember when they were building the model the question came up about how many teeth do they have, because you don’t really get to see them very clearly.

One of the employees at ILM had a pug so we brought him in, and I was trying to stretch the dogs cheeks, trying to make him do an oversized smile, so we could count the teeth, and he seemingly had an infinite amount of cheek and jowls, because as much as we would try to widen it we could never quite get them to open up, because they’re just so elastic. Eventually we were able to see what we wanted to see, but it was a fun learning experience, and that was reflected in the CG portion of the model that we married to the actual pug dog’s head.

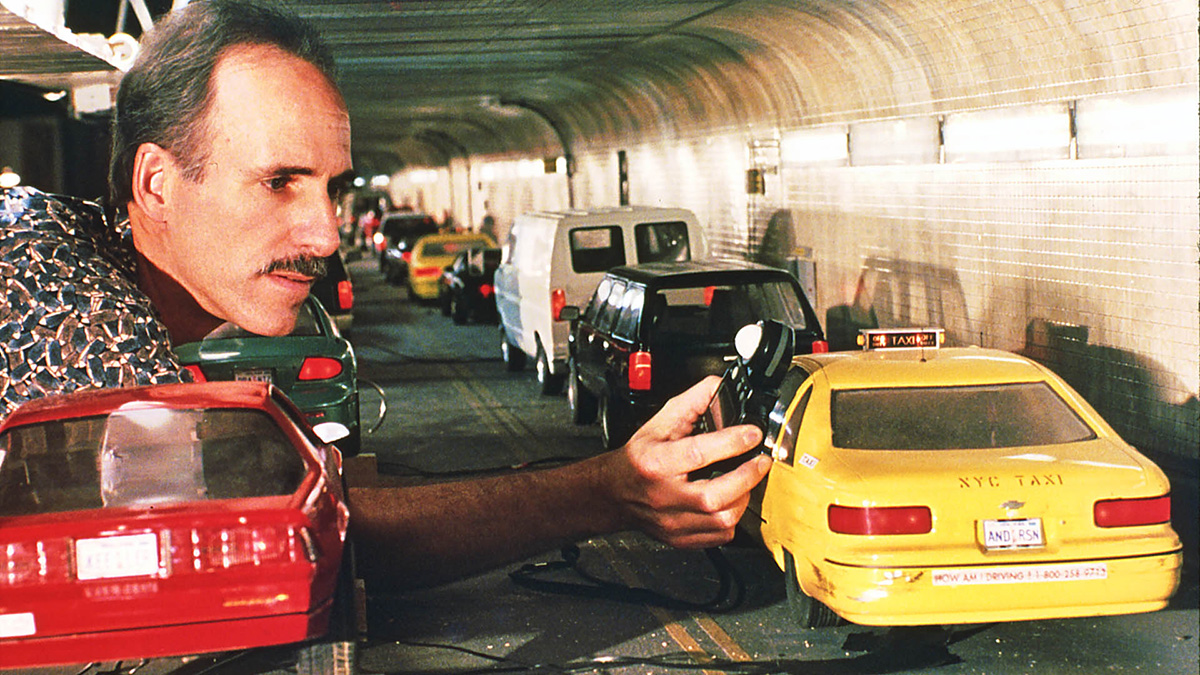

vfxblog: The car transformation sequence in the tunnel is another combo between practical and digital. One reason I love this sequence is it goes on for such a long time, and so there’s so much time to look at the tunnel and absorb the effects, which is obviously a great miniature. How did that all come about?

Brevig: In those days it wasn’t that unusual to use miniatures, but because the tunnel is so long and you have to fly a camera to an enclosed space it didn’t seem possible to be able to build a model that you could actually fly all the way through. Let’s say the camera’s moving 50 feet, I forget how long the model was, but it was probably 30 feet or more, and luckily because that was really at the stage where the ILM Model Shop, and just the craft of building miniatures, was so mature and so perfected that they easily came up with a solution, which was just a hinge. The roof of the tunnel model, I think like every two or four feet or so, there was a seam and it would end out of the way, so the entire thing could be open, so then once the camera on its crane arm passed through that area of the tunnel, they would just flip open the top of it and continue.

It was all shot motion control, so you have a long exposure and very good depth of field. It looked extremely photographically real. The cars were probably about 18 inches long, and were detailed just to perfection. That’s one of those things that because everybody knew how to do these techniques really well it was the right choice. I think that if it had been a CG tunnel, CG cars, you would have felt a little bit of a sense of artifice about the sequence.

The car that the Men in Black are driving in obviously is CG, because it’s transforming and sort of an impossible physical shape. By having the real actors photographed in a cockpit that we flipped upside down, they were going through the real physics. Their cockpit was real, the tunnel that they’re flying through is photographic and real.

It gives the whole thing this great sense of gritty New York photography, and that mixed with very broad comedy. As Will doesn’t have his seatbelt on, he’s flying around and smashing his face up against the domes, it’s just such a perfect balance between completely straight, serious top drama, and over the top comedy. I think that’s one of the reasons why it worked so well. Tommy Lee Jones is dead serious playing Elvis Presley on the radio during the whole thing, it’s a perfect absurd sequence. I remember Barry talking to Will and Tommy and saying to Will, ‘What’s the worst music that Tommy could put on just to maximise your discomfort?’ And he said, Country Western.’

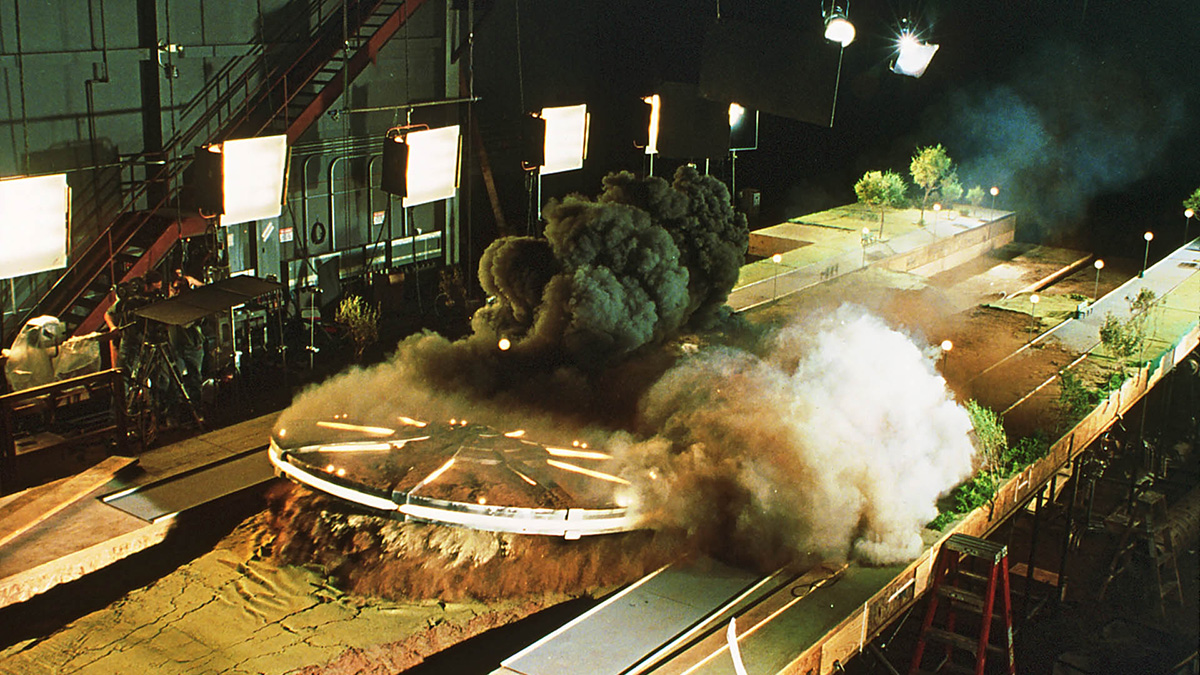

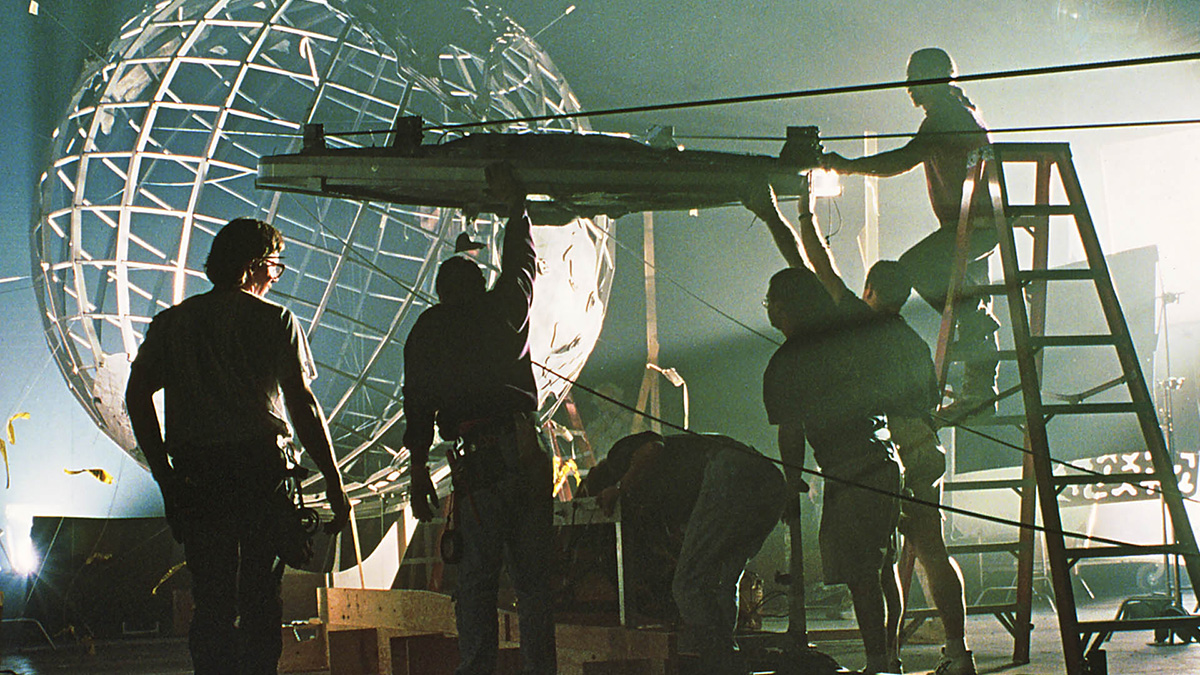

vfxblog: You used miniatures for the World’s Fair UFO crash too. It feels like that by shooting, again, for real it really established the camera moves and comprehension of the scene. There’s just a lot of time to look at it and absorb the effect, I felt.

Brevig: Yeah, because the sequence was fairly simplistic in concept the saucer crashes through this big thing, it’s called the Unisphere, it was built for the 1964 World’s Fair in a place called Flushing Meadows in New York, and it just blast through it. What I wanted to do is make it as spectacular as we could. And the Unisphere is literally a shell, there’s no logic to why it would blow up spectacularly, but I felt like it really needed to have this massive, centred, and exciting climatic scene. I said, what if it nose dives into the ground, and after it smashes through the thing it ploughs this giant tidal wave of dirt racing towards guys. Barry loved the idea. We got to have some fire in there so let’s have it blow up when it hits the Unisphere too, because that will look cool.

Once again with the model department, they all are so brilliant at what they do. We had just done a similar type of apparatus for a plane crash, so we kind of knew what to do. You build a big landscape that’s essentially full of Fuller’s earth and with those gas bombs along the way. And the camera is on a rig so that when the camera moves it pulls the model, so you know exactly where the model is in frame the whole time, and you can trigger explosions when the camera hits certain positions on its track. And then when everything is ready to go all the breakables are built and scored, and so forth. You flip a switch and you know that it’s going to work, because everything is connected to itself.

We had pyro explosions, and air mortars with dust and so forth. The majority of that shot is done in front of camera, in front of a blue screen, and then we put in the surrounding world. Then I shot the guys standing there on a little tiny blue screen at ILM after the movie was done. We did a day with Will and Tommy for their close-ups standing there with a lot of wind on them. That was intercut with the miniature with them standing blue screened in, and so the result is basically they’re just standing there as this massive thing is coming towards them.

Once again, Barry’s comedy approach is that just entirely crazy over the top things are happening while someone is completely dead to him watching it. That gave us once again both of those ingredients. Will Smith, who’s really panicked, and Tommy is standing there as though this stuff happens to him every day. Then the spectacle of what’s coming towards him really gives it the comedy. That’s the way that was set up and executed.

I still, to this day, if I’ve got any sort of large scale explosions or things with that kind of destruction, we’ll try to shoot some elements real, because I think that it just sort of raises the bar on everything, even though a lot of it is going to be CG, it establishes a bar of realism, and I think audiences react to it. Certainly the most recent Star Wars movies all benefit from a lot of full scale physical effects in a lot of places. I think that’s because we can still tell.

vfxblog: The final shot of the film is such a surprise, with the pull-out to the alien marble game. I remember that that was a very late addition. How was it added in?

Brevig: Well, what happened was, the actual original storyline was significantly changed after the first audience test screening. Initially the movie that we all shot had two warring alien planets that were alien races battling each other on opposite sides of Earth, and Earth was in the middle caught in the crossfire. There were two different names for the different races, and we never got to see them, but they were always being discussed in the Men in Black headquarters where there was a big egg shaped view screen that had all the information. There were diagrams trying to explain when one spaceship is over here, and one there, and here’s the Earth. It was just very complicated, and audiences couldn’t follow it.

After the screening, I’m not sure if it was Barry or the producers, but we all realised that since it’s all off-camera let’s just make it one alien race, and that way you have a villain that you can understand. Because all of the exposition was either in graphics that we were gonna composite onto the screen, because it was all blank when we shot it or it involved the pug dog dialogue. It was effortless to change the story because all we did was change the graphics on the screen, and what the dog’s muzzle was saying, which we were still going to animate. The plot was significantly revised with no photography needed. There was one shot at the back of the guys’ heads while they changed a word or two that Tommy was saying, but it was like the most magical, easy solution. I’ve always told people that when you have a movie that’s fairly complicated be sure to have a talking pug dog in it, because then you can fix things after with the same pose.

So adding in this final sequence was a way of adding additional complexity. Separately Scott Farrar supervised that, and the idea was just to make it all seem like we’re nothing more than a marble in somebody else’s game. That sort of brought back in the plot line that we changed.

vfxblog: A little while ago I wrote an article about some director advice that visual effects supervisors had taken on. And you told me something really great that Barry had told you, which was something about camera placement. And you said he told you, ‘Wide and low is funny, never pan, that’s not funny.’ I thought that was such great advice.

Brevig: I absolutely remember those rules, because I’ve used them in sequences that I was directing that wanted to be that same sort of comedy. Don’t let the camera work upstage the scene. It’s even more important in a comedy scene, because you don’t want the audience basically distracted from what’s hopefully a nice piece of comedy being well acted. That’s exactly what he does, he uses a wide lens, down low, locked off, and allows the scene to be funny.